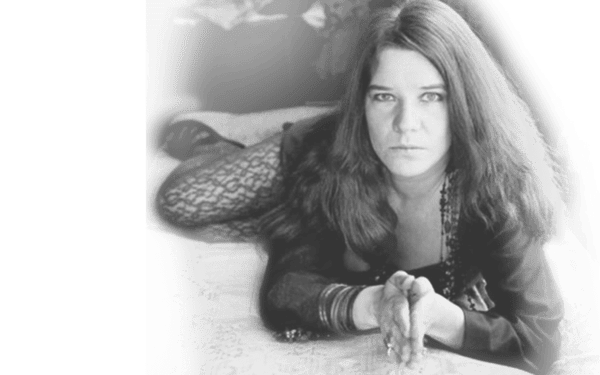

It’s been 37 years since Janis Joplin’s death in a Hollywood hotel room, and her former bandmate Sam Andrew still can’t explain it. Not the “how” — that was clearly a lethal mixture of whiskey and heroin — but the why.

“We all did drugs back then, lots of them, all the time,” says Andrew, a guitarist in two of Joplin’s groups, the Holding Company and the Kozmic Blues Band. “Janis and I in particular did a lot. It seems crazy now, and looking back on it, I don’t understand it all.”

Andrew is one of several intimate friends and associates of Joplin interviewed for Wednesday’s episode of Final 24, a documentary series that focuses on the last day in the lives of celebrities and newsmakers. It airs on cable’s Bio channel at 11 p.m.

The whiskey-voiced Joplin, who fused hard rock with blues on records like Down On Me and Ball and Chain, was one of three rock icons — Jimi Hendrix and Jim Morrison were the others — who died of drug-related causes in a 10-month period of 1970-71. Andrew thinks it borders on miraculous that there were only three.

“The real question is not why [the overdose] happened to Janis, but why it didn’t happen to a lot more people,” he muses. “Actually, it did happen to a lot more people, but they weren’t as famous as Janis.”

Joplin died alone, in the wee hours of the morning, after a night of partying following recording sessions with her new band Full Tilt Boogie that eventually became the album Pearl. Though an autopsy showed a massive amount of opiates present in her body, no drugs were found during the first search of her hotel room — a discrepancy that touched off rumors of suicide (an insurance company holding a policy on Joplin’s life initially refused to pay off) or even murder.

But most of Joplin’s friends believe the drugs were removed by a member of her entourage in a futile effort to avoid scandal.

“Exactly what happened that night is something that can’t be known, really,” says Andrew. “But probably she just got a really strong batch of heroin, which is easy to do. There were some other heroin overdoses in Los Angeles that weekend.

“The suicide theory, I always rejected that. She was happy with how her new album was going, she knew it was going to be great. She got along well with her band and they had just finished laying down the track for Me And Bobby McGee,” the song that posthumously became her biggest hit.

Andrew thinks she was just a victim of her ravenous craving for heroin.

“Janis had a big appetite for everything: living, having a good time, everything,” he recalls. “If it was food, she wanted the most and best of anybody in the room. If it was a good time, she wanted the most. She had a big appetite for drugs, too, and she had the opportunity and money to indulge it. Maybe if she would have had less of an appetite, it would have turned out better. She didn’t have a lot of caution at times.”

Not that Andrew did, either, he is quick to add. He almost died of a heroin overdose himself, and the bisexual Joplin’s longtime lover Peggy Caserta wrote in a memoir that Joplin fired him from the Kozmic Blues Band for stealing her heroin.

“I don’t remember doing that,” Andrew says. “It could be. I don’t remember it, though. Janis certainly gave me heroin — she gave a lot of heroin away . . . It’s like they say, if you remember the ’60s, you weren’t really there.”

In fact, Andrew — the only member of the band Joplin invited to come along when she bolted Big Brother to form the Kozmic Blues Band in 1968 — was so wasted that he never even bothered to ask why she fired him.

“We started the Kozmic Blues Band because we were going to write songs together,” Andrew says. “That didn’t really happen. We were both confused, doing too many drugs . . . And when the Kozmic Blues Band wasn’t working out, I was a reminder of her past. She wanted me to come along with her because she wanted a reminder of her past with Big Brother. Then I became a reminder of a past she wanted to forget.”

Big Brother was just one more noisy San Francisco Bay Area cult band when Joplin arrived from Port Arthur, Texas, in 1966 and took over the lead vocals. The band had a breakout performance at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967 and followed the next year with the smash album Cheap Thrills (shortened from Sex, Dope and Cheap Thrills by the record company). It was No. 1 when she broke with Big Brother.

Her rancorous departure, Andrew believes, was mostly a product of Joplin’s restlessness. “I suppose this may sound sexist, but women will leave,” he says. “They change things. They’ll rearrange the living room furniture every six months, where a guy is happy to live in the same room 60 years and not change a thing. Mick Jagger never left the Rolling Stones, even when he did some solo projects. . . .

“Was she more talented than the band? I think that’s a fair statement. She was the most talented person I could think of to come out of the San Francisco scene. But that also means that she wasn’t going to find a band around the San Francisco Bay Area who would have been good enough to match up with her. She was maybe even the most talented person to come out of the entire American music scene, so maybe nobody could have matched her.”

Nonetheless, Andrew — who still plays with Big Brother, along with two other original band members — admits the band’s professionalism, or lack of it, may have been a factor. “There’s just not a lot of work ethic in that band,” says Andrew. ‘ `They don’t want to rehearse,’ she used to say. It was true then, and they still don’t. She was chafing against that. She wanted musicians who were willing to work.”

Andrew is also musical director for Love, Janis, a play based on a biography written by Joplin’s sister Laura. Recording royalties and other financial considerations kept Andrew and other members of Big Brother tied closely (“like an umbilical cord) to Joplin’s family after she died, but it wasn’t an easy relationship at first.

“For a long while, 10 or 15 years, they were convinced that we had murdered Janis — that if she hadn’t known us, she would still be alive,” recounts Andrew. ‘I think when Laura began working on her book, that began to change. She talked to a lot of people around San Francisco who said, `Yeah, we were all doing heroin.’ She finally got it, that this was a culture Janis entered, and it represented choices Janis made.”

But Joplin was about much more than the drugs, Andrew adds, or even the music. “She was really a good person,” he says, noting that her appeal was so strong that the two of them became lovers after she fired him. “She was funny, a lot of laughs. We always had a great time together.”