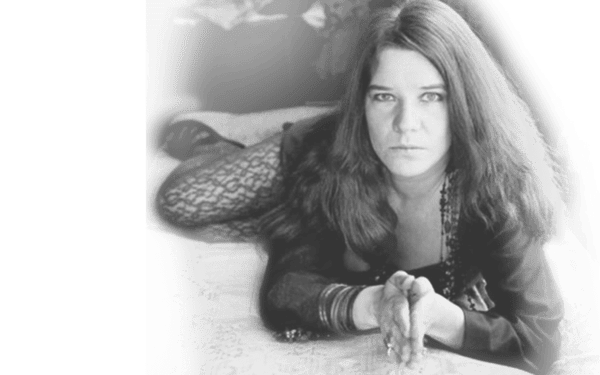

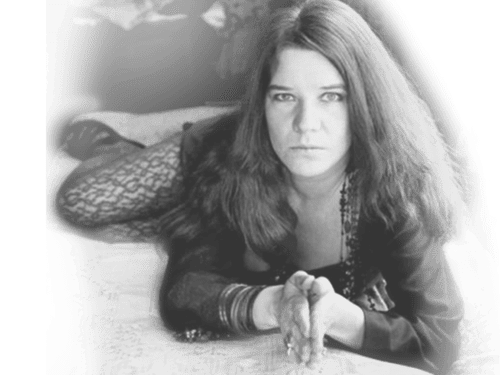

A half-acre slice of Larkspur’s Baltimore Canyon – land that legendary rocker Janis Joplin once called home – is being purchased by the county Open Space District to open a public trail that could take hikers and joggers to the top of Blithedale Ridge.

The pricey property will cost the county $411,500, according to a purchase agreement that gives the county until March 28 to raise the money.

The county started the funding push on Tuesday by dedicating $50,000 for the purchase. The Marin Conservation League also has pledged its help in raising money.

“It’s an opening of a major trailhead,” said Supervisor Hal Brown. He said he’s hopeful a combination of private and public contributions can close the gap.

The property is part of 380 W. Baltimore Ave., Joplin’s redwood-studded home at the time of her death in 1970. The hard-living rocker died at age 27 from a drug overdose in a Los Angeles hotel room.

She had lived in the wood-shingled, creekside house less than two years, but it is listed as her “last home” on Internet sites paying tribute to her and to rock landmarks.

John E. Lessin, a well-known Larkspur veterinarian, who also treated Joplin’s dogs, purchased the wood-shingled house in 1971 and lived there with his family until his death last fall.

After his death, Lessin’s son, Mike, contacted the county, which had repeatedly sought to buy land for a trailhead and an access road.

County Open Space Manager Dave Hansen said the price reflects the property’s value. The house and the rest of the lot, about another half-acre, is for sale with an asking price of about $1.5 million, said Jesse Bradman, whose real estate company, JB Properties of Petaluma, is representing the property.

Hansen said the purchase legalizes public access to a trail that people have used for years. The trail leads to the Blithedale Ridge Open Space and parts of Mill Valley and Corte Madera.

The county plans to create a new trail, steering it away from the house and around a tiny meadow.

Mike Lessin, a Corte Madera resident, said he grew up using the trail to hike into nearby open space, and the sale of the land preserves that access for generations to come.

“I wanted my children to walk through that trail,” he said. “This is a good thing for everyone. Everyone is pleased that this had worked out.”

Mike Lessin remembered moving into the house as a kid and finding some walls painted a deep purple.

“It was a trippy place,” he said.

Matt Lessin, one of his brothers, said he remembered cars from large parties lining the roads and Joplin driving her Porsche, painted in a psychedelic design, up and down West Baltimore Avenue.

Mike Lessin said he remembers hearing about sightings of Doors singer Jim Morrison and rocker Kris Kristofferson, who wrote “Me and Bobby McGee,” which become a Joplin hit after she died.

Nearly 40 years later, there are still remnants of Joplin’s short stay in the house, including a small bar made from redwood burl and wall paneling made by the carpenter who did much of the striking artistic woodwork that was featured in the interior of The Trident restaurant, a popular Sausalito watering hole during the 1970s.

There’s also a 4-foot-high dog door next to the front door that Joplin had installed for her St. Bernard. A bathroom includes a tiled sunken bath and shower below a skylight that looks out into the towering redwoods.

Joplin’s pool table still stands in the family room.

Mike Lessin said that after his family moved into the house, Joplin fans would drop by to see the place.

“Initially, it was kind of silly because it was a pilgrimage site,” Lessin said. Occasionally, he said, visitors would pocket a souvenir, usually one of the pool balls that would go unnoticed until family members would rack the balls for a game and find one or more missing.

The house is posted on Internet sites devoted to Joplin and road maps of famous rock sites such as the Grateful Dead’s Victorian on San Francisco’s Ashbury Street, Jefferson Airplane’s house on Fulton Street and the Hollywood hotel where Joplin died.

About the Larkspur house, a Web site warns: “Please do not disturb current occupants!”

Supervisor Steve Kinsey noted that securing trailheads can be expensive. They are usually slices of residential lots that pack Marin’s lofty real estate values. But they are essential to increase public access across open space, Kinsey said.

Hansen said the county had repeatedly tried to buy land or an easement from the late John E. Lessin, but he wasn’t interested in their offers.

The county occasionally negotiated permission from him to gain access for maintenance crews to an old dirt road at the end of the canyon.

Besides a trailhead, the county’s agreement includes an easement giving the county the right to cross the home site to reach the road.