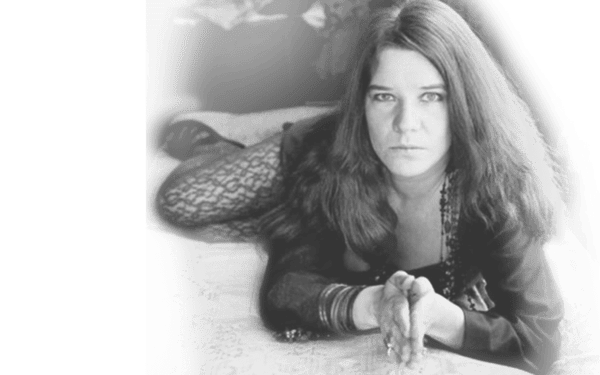

Janis Joplin was born on January 19, 1943, in a Texas town of 60,000 called Port Arthur, just off the Louisiana border. She died, presumably from an overdose of heroin, in a little plaster room in a Hollywood motel on October 4, 1970. When she died she was 27 years old.

On October 4, Janis didn’t show up at Sunset Sound Studios where she was recording a new album. Paul Rothchild, her producer, gave in to a strange premonition and sent someone over to the Landmark Motor Hotel to see why the 27-year-old blues singer wasn’t answering her phone. She didn’t respond to repeated efforts to awaken her by banging on the door so the desk clerk used a pass key. Janis was lying wedged between the bed and the nightstand, wearing a short nightgown. Her lips were bloody when they turned her over, and her nose was broken. She clutched $4.50 in her hand.

An hour later my phone rang in New York and one of her friends told me that Joplin was dead. I hung up without saying anything. I didn’t want to think about it, but all night I kept seeing – in flashes – a girl sitting in frumpy disarray in the back row of a little theater on Washington Street in San Francisco in 1966, her legs thrown over the back of the seat in front of her, chewing gum and incessantly bouncing her head to the beat of the sound which Big Brother and the Holding Company poured into the empty auditorium. Her name was Janis and she had just come up from Texas with Chet Helms who was managing Big Brother and who was trying, with a commune thing called The Family Dog, to get things together in the new world of San Francisco’s counter-culture.

The music stopped while everyone took a break. “Hey,” Peter Albin leader of Big Brother, announced, fetching the little girl and pulling her down the aisle toward the stage, “this here is ol’ Janis – the best damn singer in the world!” She looked kind of wasted for her age and she had that bittersweet heart of gold nonchalance and toughness of a beat-up old broad. There was nothing fancy about Janis: she was as down home as a body could be. Shy, and therefore apt to express herself in sudden bursts of liberated embarrassment, she always felt best standing off by herself or hidden within a group. That was five years ago and she was just joining Big Brother and the Holding Company, a favorite local blues band which made its first impact in a show called “Blast!”

A couple of months later, when Helms opened the Avalon Ballroom, Janis and Big Brother became the unofficial house band. Almost every week-end night you could fall up the stairs on Sutter Street and Wander around the blimp hangar of a dance hall and find ol’ Janis sitting over a Coke upstairs in the snack bar or leaning against a wall near the bandstand grooving away on the music. A few of the spaced-out freaks would recognize her and say a casual “Hi,” but mostly she stood by herself, straightening her rings or her antique cape like a middle-aged wall flower at a Southern V.F.W. Saturday night dance.

Guys rarely made any big plays for Janis, and even in the unpretentious society of hippies she was considered an introvert. But once in front of an audience she was the Lioness of Rock, performing dances that bore the most striking resemblance to the Kabuki dance of the lions, in which men in very long and colorful manes tossed their heads in a controlled frenzy. While all the time she belted out this stupendously shattering emotional sound. Cross-stepping from one side of the stage to the other, making an urgent sort of pleading gesture toward the audience with her outstretched hand. An agony of expression; perspired and disheveled and furious and real. Then when she stationed herself at a microphone and voiced a kind of stuttering, staggering out-cry which she had learned from Otis Redding – a singer she absolutely adored – the audience went to its feet and Janis beat an angular rhythm with one foot which punctuated and articulated the frustrated upheaval of her gigantic outpour. As a performer, she was everything we had ever hoped for in our music. She was so great that even the traditionalism of her lyrics of love, sex and loss was overwhelmed by the majesty of her style.

When Linda Eastman McCartney and I arrived in San Francisco early in January of 1968 to work on a book on rock, we interviewed Janis and the members of Big Brother. By then she had the Monterey Pop festival behind her, so Janis was beginning to understand her own power, although she was still relatively unknown. “I got a good voice,” she grunted, wiping her mouth with the back of her hand and removing her famous fur hat. “What I mean is that the pipes in my throat from here to here are made real good.” And she smiled self-consciously. “I’m learning to sing,” she continued. “I mean I’ve only been singing about a year now and so I’ve got a lot to learn. But I figure that maybe in about another three years I’m going to be a really good singer.”

On the third anniversary of that promise, Janis is no longer with us, but in her place is a newly released Columbia album called “Pearl” (KC 30322) in which she has kept her promise. She has become a really good singer.

In every previous recording by Joplin, from the first album, Mainstream’s rip-off fiasco, through Columbia’s early and awkward pair of efforts to record this great blues singer, the results were far less than what devoted fans demanded of the perfect Joplin disk. But “Pearl” fulfills our every expectation. The album is nothing short of a total smash! gone are the fake acoustics which flawed Janis’ voice. Gone is the least trace of amateurism, instrumental or vocal. Gone too, praise the Lord, the souped-up horns and other phony paraphernalia of imitation soul accompaniment. What’s left is pure Joplin performing with the superb Full Tilt Boogie Band.

In cuts like “Cry Baby” and “My Baby” we find the big, throaty Janis we knew in the very beginning: pleading, snorting and sobbing her reckless way toward a bigger and bigger musical climax. In “Half Moon” we meet the new and consummate Joplin who has so perfectly balanced control with emotional exuberance that she reminds us a bit of the best of the old-time jazz singers.

But the high point of the album commences with the second cut on the second side, “Me and Bobby Me Gee,” which gives both Janis and songwriter Kris Kristofferson a fast and firm place in musical history forever. It continues to soar to unbelievable theatrical heights with the intimacy of Janis’ own song, “Mercedes Benz,” sung without accompaniment, followed by an avalanche of expressive sound which tumbles out of the song, “Trust Me.” And finally the ironically climatic “Get It While You can.”

The Full Tilt Boogie Band is the perfect group to back Janis. And though their solo instrumental leaves me cold, I’m knocked out by the musical partnership between Janis and the band which managed to come into fruition in just three short recording sessions. Special mention should go to pianist Richard Bell and drummer Clark Pierson without in any way minimizing the fine musicianship of everyone involved in the recording. And in light of the false starts, near-misses and mediocre results of prior Joplin recording sessions, producer Paul Rothschild surely deserves a citation of honor.

Janis Joplin successfully revived an old cliche for the new generation. She was the ultimate embodiment of our sense of tragedy: a concept by which to measure pain. We chose her as the quintessential loser and she perfectly and willingly fit the role. She never disappointed us, not in the tragic nature of her death nor in the ironic perfection of her last album, “Pearl,” the name by which some of her intimates knew her.

But for me the name has a different significance. Abrasive and constant irritation produces pearls; its a disease of the oyster. Gustave Flaubert said that the artist is a disease of society. Janis was a disease of America’s gigantic loneliness. She is pearl.

I last heard from her a few weeks before her death. She was in Los Angeles where I was working, too, and she asked me to come have a drink with her at a seedy little bar across the tracks from the groupie-infested Tropicana Motel on Santa Monica Boulevard. Kris Kristofferson and I spent a couple of hours with her and then we walked her across the tracks back to the shabby room where she crashed almost as soon as she hit the bed. I remember I was frightened by her massive fatigue. “are you all right?” I asked. She half-opened her eyes and smiled bitterly. “Sure,” she muttered, “I’m working on this tune,” she mumbled in her rusty voice. “I’m gonna call it something like this: ‘I Just Made Love To 25,000 People, But I’m Going Home Alone.’ ” Then she went to sleep.

Damn you, Janis Joplin! God damn you for leaving us so soon!

Also in Jan. 31, 1971 New York Times pg 21 large photo of bearded man giving tattoo to young woman with a large poster of Janis behind them: “A Joplin Cult? San Francisco tattooist Lyle Tuttle decorates a client with the same heart-shaped tattoo he did for the late Janis Joplin. Tuttle, to be interviewed on NBC’s “First Tuesday” at 9 pm, says more than 100 girls have asked for the tattoo since the rock singer’s death last fall.”