James Gurley has been dragging a ball and chain around for almost 40 years.

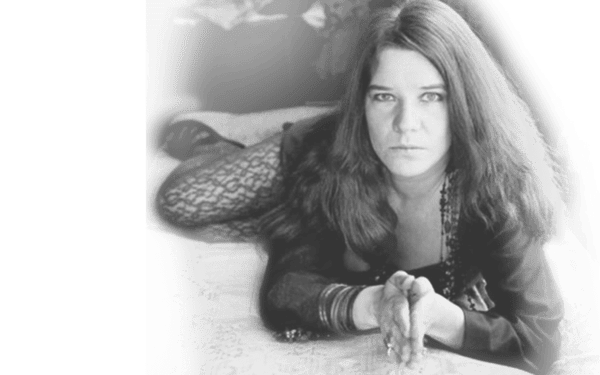

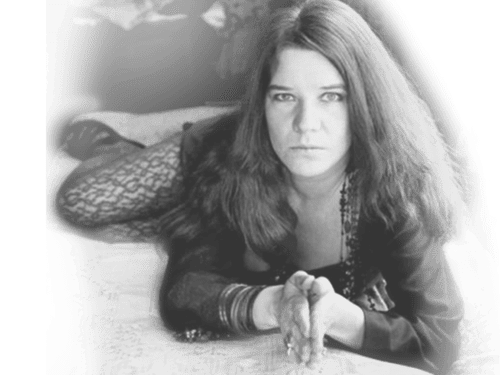

He was a guitarist, arranger and engineer of Big Brother and the Holding Company, the San Francisco band that featured a gutsy, amazingly soulful lead singer named Janis Joplin.

Clive Davis, the record mogul for Justin Timberlake and all of the “American Idol” winners, signed Big Brother to Columbia after being mesmerized by Joplin at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival. Their first album, “Cheap Thrills,” went to No. 1 and sold more than a million copies.

Joplin was a vocal progenitor, but Big Brother helped pave the way for today’s rock jams bands. And Gurley was the only band member to earn an engineering credit on “Cheap Thrills.”

But critics said Gurley and his bandmates didn’t measure up to Joplin and Joplin agreed. She left the band after that one album.

Gurley became embittered. The Joplin myth grew after her death in 1970 while Big Brother faded from memory. Gurley moved to Palm Desert in the 1970s and became godfather to the desert punk scene. He returned to the Bay Area and just came back after 20 years. He and his wife, Margaret, now make a living as fine artists.

Gurley learned last month “Cheap Thrills” is being inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame as a work by Big Brother and the Holding Company. A committee of diverse recording arts professionals called it a “recording of lasting qualitative or historical significance.”

The Recording Academy Trustees mad it one of 44 works from 25 years ago or more to be added to their list of the 728 best recordings of all time.

Gurley is pleased, but cautious about getting excited.

“I like it,” he said at his Palm Desert house. “It’s a little bit of recognition. But most of it’s going to go to Janis. I know that.

“I mean, Janis is in the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, but we’re not. They invited us to come and play for the induction of her. And we did it. My picture’s in there with her, but I’m not in the official list of inductees. That hurts.”

Roots of hippie rock

Gurley was an important part of San Francisco’s rock scene even before teaming with Joplin.

Rock ‘n’ roll and folk acts generally played coffee houses or variety shows before several West Coast promoters converted ballrooms into large venues for rock ‘n’ roll dances in the early ’60s.

Gurley was one of the original artists, along with Jefferson Airplane, asked to play at San Francisco’s first ballroom rock dance in 1965 by Chet Helms, who became Big Brother’s manager.

Big Brother became the house band at Helms’ Avalon Ballroom. Like the fledgling Grateful Dead at Bill Graham’s Fillmore ballroom, they played improvisational sets.

Gurley was inspired by seeing jazz saxophonist John Coltrane play at a coffee house in his native Detroit in 1963. He recalled listening to his band for two or three hours before his sidemen just got up and left. Coltrane was still playing when Gurley got home and called the club.

“I heard a lone saxophone raging like a madman,” Gurley recalled. “I said, ‘That’s the way to play, like a madman.’ And that’s what developed my style: Play it like crazy.”

Gurley has been called the father of the psychedelic guitar for his fiery improvisations, but jazz influenced him more than drugs. San Francisco, where Gurley moved after a stop in Los Angeles, was a serious jazz town. Big Brother’s Dave Getz had been a jazz drummer, as had the drummers for the Airplane and Quicksilver Messenger.

When musicians got together, they created songs from riffs that came out of jam sessions. Jazz players had been doing this for years, but pop artists from Elvis Presley to Andy Williams got songs from writers who composed alone. Even The Beatles played songs they wrote in advance instead of going on stage with just an idea for an improvisation, like jazz artists.

“The whole San Francisco scene was really much closer to jazz,” said Gurley. “That was the time the music changed from being pop rock ‘n’ roll to where the jazz influence became apparent.”

Finding Janis

Big Brother’s challenge was finding a singer who could be heard over their loud improvisations. The PA systems were mostly 100 watts, compared to the many thousands of watts PA systems have today.

Gurley suggested a singer he had heard in a coffee shop a year before. He had recorded her singing blues, gospel, bluegrass – “all the things we were into.”

Helms recognized her as an acquaintance from Texas and had a friend bring her back to San Francisco. That’s when Janis Joplin joined Big Brother and the Holding Company.

“She said, ‘I need songs, I need words. I can’t just make it up all the time,'” said Gurley. “So we decided, ‘We’ve got to do organized songs to a certain extent. We can branch out, play crazy in the middle, but we’ve got to have words and lyrics.'”

They already had a contract with a small label. But Bob Dylan’s manager, Albert Grossman, and Clive Davis convinced them to sign with Columbia after hearing them at Monterey Pop. They offered $100,000 to get out of their contract, with rest coming out of future earnings.

“So, instead of getting an advance, we got a debit,” Gurley said. “We went into the thing $150,000 in debt!”

The album contained songs that still hold up today. “Piece of My Heart” became a hit single. “Combination of the Two,” “Ball and Chain,” “Summertime” and “I Need A Man To Love” all became classics.

Classic but maligned

But the jazz-influenced instrumentals were something way different from jazz. The critics immediately assumed that was bad.

“I don’t know of any band that has been so maligned as Big Brother,” Gurley said, “not even Milli Vanilli and one of those guys killed himself. We don’t get appreciation for all the arrangements we did and all the engineering tricks I came up with.

“We were denigrated for being out of tune. Well, we were totally stoned on drugs and alcohol, but they didn’t say that about The Beatles. Listen to ‘Paperback Writer.’ Listen how out of tune those guitars are. I never heard anybody say, ‘Oh, this is (crap) because they’re out of tune.'”

Record executives already doubted that a rock band could write and arrange their own music. Most of the L.A. bands, such as Sonny & Cher and the Mamas and the Papas used studio musicians with jazz credits.

Joplin started thinking maybe they were right. “I’m sure Clive Davis thought, ‘We could get some studio musicians and do better’ – back to the old way of thinking,” Gurley said. “She bought into that and, a year later, it was all over. One album and it was gone.”

Joplin had only one top 10 single after going solo. “Me and Bobby McGhee” hit No. 1 after she died of a heroin overdose.

The remaining Big Brother members had several reunions before Gurley left the band for good in 1996. He regrets now he didn’t support his colleagues’ idea to hire a female singer to replace Joplin. “I was feeling so hurt and depressed from the breakup,” he said. “I’m sitting there in San Francisco and, ‘Oh, God. This doesn’t feel good.’ That’s when I really got into drugs heavy.”

Gurley has long since overcome his addiction to heroin. The only hallucinogenic in his life now is the reflective art he calls “psychedelic dreams.”

But he hears reminders of his past all of the time, from the jam bands from Seattle to the vocal stylings of Davis’ latest stars.

“I hear a lot of guitar players and I go, ‘That guy has heard me,'” Gurley said. “We were at Best Buy last week and they were playing ‘Summertime’ by Christina Aguilera with our arrangement. She did a total cop of Janis’ style, which was done in the context of Big Brother.”

The Grammy induction doesn’t erase the painful memories, but it dulls them. “In a lot of ways, it seems like another world, another person did it,” Gurley said. “Other times, it seems like yesterday.”

Gurley ‘s link to Joplin

James Gurley still has the reel-to-reel tape he recorded of Janis Joplin before she joined Big Brother and the Holding Company in the mid-1960s.

He discovered it in 1996. It featured a Joplin the world hadn’t heard, with a pure voice unravaged by drugs and rock ‘n’ roll, but still containing her incredible depth and soul.

He spent years adding a band to her vocals. His friend, Ming C. Lowe says, “An unexpected quiet and genuinely sweet Janis comes through.”

“It’s unheard Janis Joplin material,” Gurley says. “It’s probably the best album she’s done since ‘Cheap Thrills.'”

But Gurley won’t release it because of the litigation his lawyer said he’d encounter from the Joplin estate over ownership of the album.

He says he couldn’t get Columbia to release it without Joplin’s sister’s support. So he keeps it for himself and friends.

“It was a work of love,” Gurley said. “I wanted it to be something, if she was looking over my shoulder, she would be proud of. I tried to keep her first and I didn’t change what she did.

“This is what she was doing before Big Brother. I wanted to bring out that innocence before she got crazy from rock ‘n’ roll.”