DENVER – Janis Joplin loved to knit. She read Time magazine every week because her father told her it was a good way to stay in touch with society. She wore her hair in a bouffant during one of her brief college stints, when she studied sociology and art.

She and her younger sister, Laura, spent hours in front of a mirror trying on clothes and doing each other’s hair. When she was away from home, Janis wrote caring letters to her mother.

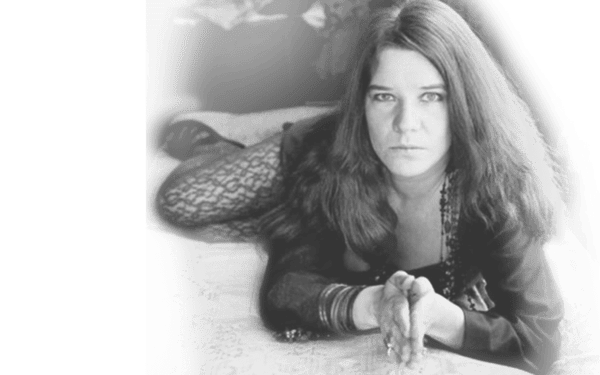

Janis Joplin was a rock ‘n’ roll star, a brassy blues mama who died of a heroin overdose in 1970 at age 27.

Now Laura Joplin, six years younger than Janis, has written a biography, “Love, Janis” (Villard, $22.50), that puts the hometown girl Janis and the Janis who personified the rebellious 1960’s on the same coin.

“Janis is an image of the psychedelic music, drugs, emotional freedom of the 60’s,” said Laura, sitting at the dining room table in her comfortable Denver home, where she lives with her husband and young daughter. “There is a renewed interest now in that time and in Janis…

“She believed that no matter who you are – race, dress, pimply face, whatever – everybody deserves equal respect and love. People in the 1990’s are searching for that kind of connection after the materialism of the 80’s.”

Laura, who has a Ph.D. in education from Prescott College in Prescott, Ariz. decided to write the book to give a “fuller and more balanced view” of Janis than other biographies presented. The writing also helped her resolve the grief over her sister’s death in October 1970.

“Writing the book was a turning point for me in that I moved past the grief and came to a broader and deeper appreciation of Janis,” Laura said. “Now I can listen to her songs with joy, instead of crying.”

Laura hopes the book also will change people’s perception of Janis. “Many people have a hard time getting past the confrontation, free sex and drugs of the 1960’s scene. They dismiss Janis as just being a hedonist hippie of that time,” she said, with a touch of East Texas softness in her voice. Her mother still lives in Port Authur, Texas, the Gulf Coast town Janis left after high school but returned to several times between stints at college and trips to California.

But Janis and the musicians of the San Francisco scene had a philosophical base for what they were doing, according to Laura. They believed that by breaking sociological and emotional barriers in their personal lives, they could learn more about themselves. If enough people did that, then society would change to be more open and accepting.

“The impetus of the personal growth movement, feminism and the environmental movement came from the 1960s,” Laura said, “although many of the people back then, Janis included, didn’t know what they were doing. They acted impulsively.”

But according to Laura, Janis deliberately turned away from the intellect to focus on the emotional self.

“Being an intellectual creates lots of questions and no answers,” Janis is quoted in the book as saying. “You can fill your life up with ideas and still go home lonely. All you really have that really matters is feelings. That’s what music is to me.”

Janis came by her musical inclinations naturally. Her mother, Dorothy, had an operatic soprano voice and appeared in college musicals. A New York theatrical director heard her sing and encouraged her to try a stage career. Instead, after graduation, she got a job at an Amarillo, Texas, radio station, where she met her future husband, Seth.

The couple moved to Port Arthur, where Seth got a job as an engineer at the Texaco refinery.

“Our father taught us to ask why things happened or were as they were,” Laura said. “He was tone deaf, but had a fine sense and appreciation of classical music. Our parents never pushed music on us, but mother would show us singing techniques.”

Those singing lessons came at odd times. “On Saturdays, when we cleaned the house, mother would put on records of Broadway showtunes full-blast. She, Janis and I did the work singing at the top of our voices,” Laura said.

Despite all the singing around her, Janis’ early artistic interests were drawing and painting.

“Being an artist was Janis’ goal and more than in just the technical sense,” said Laura. “She had the mindset of an artist.”

But being an aspiring artist in Port Arthur (pop. 55,000) in the early 1960’s, especially for a young girl from a respectable family, set Janis out of the mainstream. In high school, she taught herself to play the guitar, wore black turtlenecks and hung out with a gang of self-styled beatniks.

Janis bought recordings by Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday. She went to the Cajun and black nightclubs in Vinton, Louisiana, just across the state line, when she was still underage. Blues was performed in black nightclubs in Port Arthur, but “white girls didn’t go there nor would they have been welcomed,” said Laura. “Port Arthur was very segregated until 1967.”

Janis’ first public performance, at a park department talent contest in the summer of 1962, was in Austin, where she was attending the University of Texas.

Previously, she had attended Lamar State College of Technology (now Lamar University) in Beaumont, Texas, and Port Arthur college for a couple of semesters.

By 1966, the psychedelic scene was burgeoning in San Francisco, where the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane and other bands were attracting national attention. Janis was urged by rock impresario Chet Helms to head west and check out a San Francisco band called Big Brother and the Holding Company, which needed a vocalist. Janis left school once again and headed for the coast. Six days after she arrived, Janis joined the band.

She found herself in the middle of Haight-Ashbury and a creative explosion that promoted self-exploration, free sex as communion, racial integration, an anti-establishment attitude and music as ecstasy, Laura writes.

Laura visited Janis in San Francisco during the so-called Summer of Love 1967, when hippiedom was in full bloom. Drugs and alcohol were used to tap into emotions and creativity.

“It was a very eye-opening experience. I had never seen stoned people before,” recalled Laura, who stilled lived at home then. “I was getting ready to go to Lamar in the fall of and the hippie culture had not yet spread to Texas. Janis was exuberant, showing me Haight-Ashbury, taking me to the clubs, signing autographs on the street.”

Big Brother was a successful act by that time, earning good money and good reviews. But it was the band’s performance at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967 that made Janis famous. The following week, she was written up in Time magazine. The album she made with Big Brother in 1968, “Cheap Thrills” sold more than 1 million copies and spun off the hit single “Piece of My Heart.” She began a solo career in 1969 and released just one album before her death.

The fame damaged Janis and Laura’s relationship with her, Laura said.

“Janis started to get an attitude of “you’re hip or you’re not,” Laura said. “In 1970, she said in a interview that our brother Michael (today an artist who works in glass) was hip but I was not. I was indignant at being branded unhip. I had very heated words with her.”

Laura wasn’t that unhip. She tried some singing and “had my hippie experience,” she said with a laugh. Part of her experience was living in the mountains outside Boulder, Colorado, building log cabins and developing an Outward Bound-type educational program at a summer camp as part of her doctoral work.

“I idolized Janis and followed her around everywhere when we were kids,” said Laura. “But I didn’t need to follow in her footsteps. I didn’t need singing like Janis did.”

As passionately as Janis sought stardom, she quickly became disillusioned by it and by the public image she cultivated as a fast-living red-hot white woman singing the black blues, Laura reports.

“She thought (the public image) was a cheap sell,” Laura said. “she tricked herself out in sexy clothes showing lots of cleavage and all of a sudden, ta-daaaa! She arrived. She was the same person singing the same songs. Her own artistic temperament said, ‘I want to relate with your guts. I really want to get into it.’ And here she was riding a crest of success built on all the other stuff.”

Janis tried various genres but she always returned to the blues, which offered her a way to get in touch with her elemental self: “She always remembered that the God in her was talking to the God in you,” said Laura. “The spiritual quality of the blues allowed that expression. Music has the potential for unleashing the spirit and Janis found that music worked her that way.”

Janis died on a Saturday night in Hollywood’s Landmark Hotel. in the book, Laura, working from accounts of friends and the coroner’s report, describes the moment: “Janis sat on the bed clad in a blouse and panties. She put the cigarettes on the bedside table, and still holding the change in her hand, she fell forward. Her lip was bloodied as she struck the bedside table. Her body became wedged between the table and the bed.”

Earlier in the evening she had injected heroin, a drug she used on and off for years to relax during recording sessions. Her other drug of choice was Southern Comfort, to such an extent that she acknowledged being an alcoholic.

She had bought the heroin from her usual dealer, George. As a rule, he had a chemist check out the drug before he sold it, but that night the chemist was out of town. The dope Janis bought was 4 to 10 times stronger than normal, Laura writes in the book. That weekend, several of George’s other customers died of heroin overdoses.

“I look at her death as this horrible mistake,” said Laura. “She wasn’t depressed or frustrated. She was making plans, looking to the future. She had had her hair done.

“People make her out as a tragic figure because she died of drugs. They forget that being around Janis was having a good time. She was a avery upbeat, exciting person. She was always fun, a memory I have of her from the earliest days in the family.”

Joplin came to symbolize the right to fully express yourself without fear.

In the book, Laura quotes a fan’s letter: “She’s us. She’s not a star, she’s us. I’ve never met her but I know her. It’s like, hearing her, you leave your body and you just move, man. She’s just all energy.”