The orthodox pop theory is that Janis Joplin died at the proper moment, just as her personal incandescence and megavolt voice were about to burn out. This is nonsense -as her album “Pearl” released after her death, attests. Other myths cling too – not surprisingly, since Janis cultivated them with the same passion she collected “pretty young boys” at her favorite bars. Two biographies since her death – David Dalton’s worshipful “Janis!” and Peggy Caserta’s trashy “Going Down With Janis” – have added only confusion.

Myra Friedman’s intelligent, deeply felt book should set the record straight. Few people are better qualified to attempt a Joplin biography. The two women met in 1968, shortly after Friedman went to work for Janis’ manager, Albert Grossman. “I adored her,” writes Friedman. “She was intemperate, impetuous, kaleidoscopically wild, registering like a haywire neural encephalogram.” The author, whom Janis called her “Jewish mother,” went with the superstar on concert tours, shopped with her, drank with her, commiserated with her – and understood her.

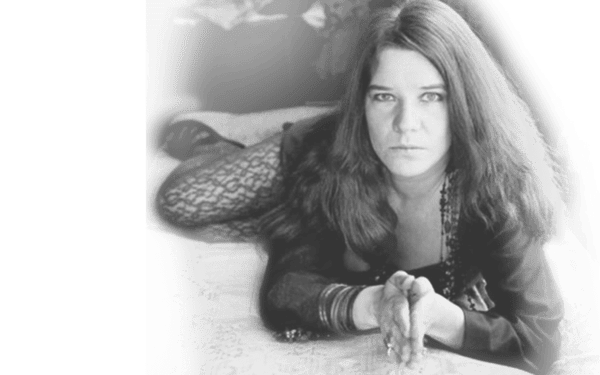

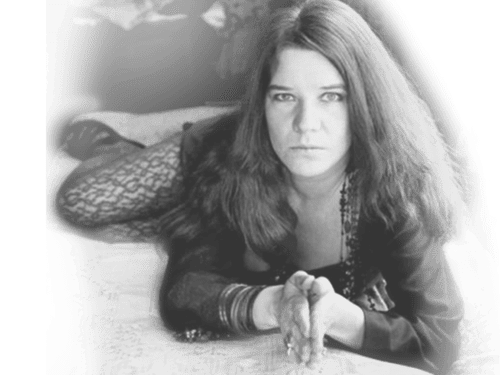

Friedman knows that audiences create superstars to embody their own fantasies, and Aphrodite was Janis’s assigned role. Her performances reeked of sexuality. She stomped, shimmied, swung her hips, and screeched carnal knowledge in a voice as gritty as a Texas dirt road. Offstage it was the same. She aggressively pursued any male or female she desired. She became the libidinous Earth Mother to a generation of gentle dreamers.

A terrific act but, as Friedman points out, only an act. The adjectives she uses to describe Janis are “insecure,” “lonely,” “desperate,” “anxious.” On the basis of interviews with Janis’s parents and people who knew her in her native Port Arthur, Texas (where her nonconformity was deplored,) with those who knew her at the University of Texas (where she was a nominee for Ugliest Man on Campus) and those who knew her professionally, Friedman concludes that Janis believed she was ugly and “was in need of an unrelenting testimony to her appeal.” In her war for acceptance, sex became the battlefield. And suggests Friedman, fears of homosexuality created “overcompensation the other way.” The inner emptiness persisted and she tried to fill it, first with booze and speed, later with more booze and heroin.

Habit: “Chronic suicide,” writes Friedman, “is what Janis was engaged in throughout her life.” Occasionally Janis would see a doctor about her alcoholism (which obscured her drug problem from the public) or visit a psychiatrist in an effort to kick her heroin habit (she tried methadone programs unsuccessfully.)

As though trying to exorcise any guilt she may feel about Janis’s death, Friedman carefully reconstructs the final months, analyzing them for signs, portents, omens. ironically, Janis struck the needle in her arm just when things seemed to be going well for her. She was ripening saw an artist. she was making plans to marry socialite Seth Morgan. She had been off heroin for five months. Yet she remained unhappy. “If it doesn’t get any better,” Janis told her friend Kris Kristofferson, “I’m gonna go back on junk.” The coroner ruled her death accidental, but Friedman believes “her death was an accident in only the most marginal use of that term.”

Friedman is a gifted writer although her prose at times seems to run a temperature of 110 degrees. To read this deeply moving book is to understand how much Janis’s art expressed her tragic life. Its title derives from one of her favorite songs: “All caught up in a landslide, bad luck pressing in from all sides/Got bucked off my easy ride, buried alive in the blues.”