Four months after a play based on the life of the singer Janis Joplin was closed because of a lawsuit by the Joplin estate, a Federal judge here has ruled that the production is a protected form of free speech.

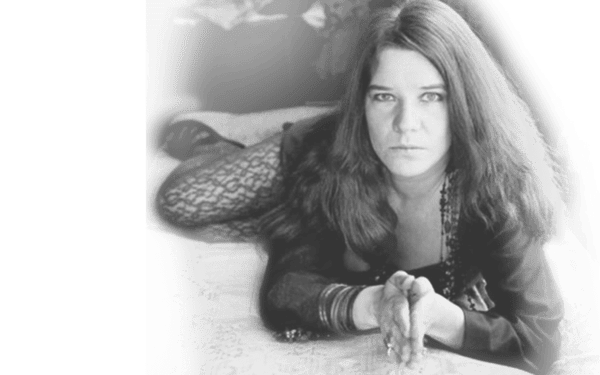

The ruling on Monday, by Judge John C. Coughenour of Federal District Court in Seattle, is one of the few nationwide in which a court has tried to define the commercial rights of a celebrity’s estate. Joplin, the Texas-born blues and rock artist, died of a heroin overdose in Hollywood in 1970 at the age of 27.

Joplin’s family, joined by Manny Fox, a New York producer who owns the rights to make a film and play based on her life, asserted that the Seattle theater company could not stage the play “Janis” without permission of the estate. In the suit, the estate claimed “the exclusive right to exploit stage productions, theatrical films and television productions based on the life and times of Janis Joplin.”

The central legal issue is the “right of publicity,” which grants an estate control over a dead celebrity’s name and style. Only a handful of states have enacted such laws, and they are usually limited to T-shirts and souvenirs, not artistic expression.

In this case, the judge cited California’s law, which exempts plays, books or musical compositions from the right of publicity. That law, Judge Coughenour wrote, applies only to merchandise, advertising and endorsements. When the celebrity’s name is used in a play, it is a protected form of free speech, he wrote. The Broader Effects

The decision leaves open the question of copyright infringement for two songs that were used in the play. The estate says the producers did not have full permission to use the songs.

The case touched on issues likely to affect anyone seeking to capitalize on the life and career of a dead celebrity, from the legions of Elvis Presley imitators to impersonations by comedians.

“Janis,” written by Susan Ross, a first-time playwright who lives in Seattle, was a small non-Actors’ Equity production that ran from May 30 to Aug. 18, when it was closed after the suit was filed. Ms. Ross, joined by civil liberties and anti-censorship groups, said she had the right to create her own work of fiction based on Joplin’s life.

In the first half of the show, Joplin, played by a Seattle nightclub singer, Duffy Bishop, is seen daydreaming, talking with Jack Kerouac, Mae West, Zelda Fitzgerald and others. In the second half, she is depicted in concert, singing 11 songs that were trademarks of Joplin’s act.

Mr. Fox said the suit was filed “for the same reason the Disney Company protects Mickey Mouse: the right to protect what you own.”

“Our position is that this is a concert with a tack-on first act to give it free speech protection,” he said. Mr. Fox is developing his own production, “Love, Janis,” for Broadway in 1993, when the singer would have been 50 years old.

But civil liberties groups said the suit would have a chilling effect on any artistic production that made use of a celebrity.

“The estate’s claim violates the freedom of expression protections of both the United States and Washington State Constitutions,” said Julya Hampton of the American Civil Liberties Union, which filed a brief on behalf of the playwright. “It would be like saying that the estate of Richard Nixon could someday control all artistic portrayals of him.”

Another group, the Washington Coalition Against Censorship, said in a statement, “If the Joplin estate prevails, no author, producer or performer will be able to write, produce or perform a piece of fiction based on the life of a public figure without permission. The existing and potential works of many authors and playwrights will be effectively suppressed.”

After the ruling, Ms. Ross said she would like to revive her production, which played to good crowds in a small theater and cost less than $60,000 to produce.

“A lot of artists are very naive about the law,” she said. “I know I was. And the implications of this are enormous, when they can force you to shut a play down. Now, with this ruling, the judge is saying you are free to write your play.”

Mr. Fox, who produced the play “Sophisticated Ladies” in the early 1980’s, said the judge’s decision would be appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, in San Francisco.