Can you picture James Dean, can you imagine Janis Joplin, grown old and wheezy and boring, trying to deliver clever patter on late-night talk shows? Horrid image. No, far better to have them in our minds now as smashed idols, as icons of their separate fiery moments.

You think of Janis Joplin, whose music is so redolent of the ’60s, and what comes to mind? A woman who could bellow and cry and stamp and then turn around and go achingly tender. Someone who could sing up every song any truck driver ever knew. Someone in whom there seemed so much need, which somehow she transformed to our need.

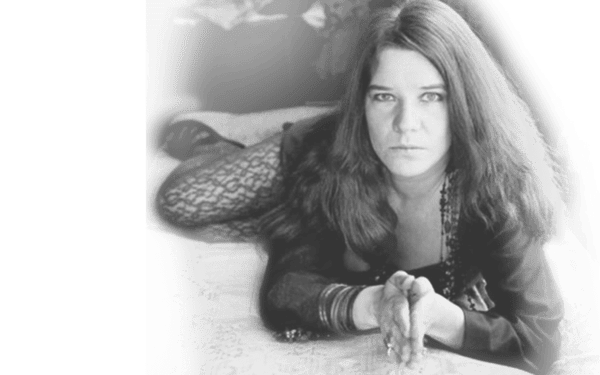

You think of that sweaty and sometimes porcine face. Of the bad complexion. Of the tangled hair. Of the mouth eating the microphone. Of the pink feather boas. Of the layers of bracelets. Of the tattoos. Of the fifths of Southern Comfort carried onstage. Of that wild hillbilly cackle. (Remember how she just dissolves into it at the end of “Mercedes Benz” on her last album, as though everything, not just the ditty, but life itself, were so damn absurd?) Janis Joplin had an incredible cackle. She had a cackle like no one else in rock. It’s one of the clues to the other self.

Sometimes, though, she could be surprisingly beautiful. Physically beautiful.

Was she selfish? You bet. Was she sexual? To her toenails. Was she self-destructive in both her pursuit of sex and her turned-inward lifestyle? “She defined men sexually, as she defined herself, and then went at her one-night stands and sometimes orgies under the cover of a liberated style of life. . . . She was left with little more than the yawning chasm of a tortured loneliness,” her publicist and biographer, Myra Friedman, wrote after Joplin’s death in one of the very best books about her. It’s titled, not wrongly, “Buried Alive.”

Friedman, who knew her intimately for years and cared for her deeply, says her friend was afflicted by “an emotional astigmatism. Each second was clear, but there was no focus.” That could stand as an epitaph for the ’60s themselves.

But past all the deep character flaws and time-bomb self-destructs, there was her music. It doesn’t seem too much to call her the greatest white blues mama who ever lived. She wasn’t so much a writer of blues songs as she was a practitioner, an interpreter. “When I’m there, I’m not here,” she once said. “I can’t talk about my singing. I’m inside it. How can you describe something you’re inside of?”

Which is why she didn’t really die back there in that cheap hotel in Los Angeles 28 years ago. Which is why she’s able to haunt us yet, with a little piece of her heart. She’s got us on her ball and chain. She keeps wailing in our ear, Cry, Cry Baby! According to the family members who control her estate, her record sales have increased every year for the last decade.

Our fascination won’t let up, even now, in these Webbed-up, rapped-up ’90s.

The Smashup

She died alone, late at night, in her panties and blouse, loaded up with extremely pure heroin, plus some Ripple wine and vodka. Could a picture be more squalid? Yes, frankly. When they found her that Sunday evening, many hours after the fact, she was wedged between the night stand and a bed that was slightly askew of its frame. This was in the Landmark Motor Hotel in West Hollywood. Her lip had been bloodied in the fall and her nose appeared to be broken. In her fist were some dollar bills and silver: She’d gone out to the lobby to get change for a five so she could buy a pack of cigarettes. The guy at the desk was apparently the last person who ever spoke to her.

She came back to her room – it was about 1 a.m. – got partially undressed, perhaps sat down on the bed, perhaps reached over to put the smokes on the bedside table, then pitched violently forward. “Like a puppet hurled down or kicked over,” Friedman wrote in “Buried Alive.”

“Buried Alive in the Blues” was the tune Joplin and her new band, Full Tilt Boogie, had been working on in the studio that weekend. It was Oct. 4, 1970. At 27, the life was gone, the legend was born.

No, that’s not quite it. The Joplin legend – as “genius and junkie, rock diva and drunk,” again to quote from Friedman’s book – was born long before her death (which, as it happens, followed Jimi Hendrix’s squalid and appalling end in London by a little more than two weeks). But the aloneness and middle-of-the-nightness of it, and then of course the overdosing with the needle, only intensified the myth, elevated it, sanctified it. America wants doom like this, no matter the collective head-shaking as to tragic wastefulness. It’s the stuff of our pulp dreams, of our baser selves.

Somehow we wish our James Deans to buy it bad in a silvery Porsche Spyder on the road to Paso Robles. A head-on auto accident claimed Dean, who was on his way to a California auto rally. He was gone at 24 in 1955, with just three movies made yet the myth already stratospheric. Joplin’s end, in California, at the end of the next decade, of the rock-and-roll decade, of the psychedelic decade, was head-on, too, only in another way. As film critic Richard Schickel has written: “There is much to be said for dying young in circumstances melodramatically appropriate to your public image.”

On the night of the needle, she didn’t shoot it into a vein; she skin-popped it, so as to obtain a delayed and oozeful rush, up to 90 minutes.

What would you bet that the tawdry thing that happened at the Landmark is going to show up (in a theater near you) in one or both of the competing Joplin film projects now seriously in the works? Janis keeps reappearing in new guises and cultural forms – books, movies, plays, new/old recordings.

Okay, as an icon, she’s not the Kennedys or Marilyn Monroe, not even close. But consider: In the last few years there have been as many as four movie projects in development, though now there are only two major contenders. “Piece of My Heart” has Courtney Love slated for the lead role; it may start shooting in the fall. Somehow, she seems all wrong for the part. She’s too tall. The blues vortex isn’t deep enough. (The other film project reportedly has Lili Taylor starring.)

Todd Gitlin, author of “The Sixties,” which may be the definitive work on that messy, rageful, hopeful decade, said the other day on the phone, thinking of Joplin and the strange way she endures: “Listening to her is like being sucked into a vortex. She goes deep. That deep throaty depth. I’ve listened to a lot of blues. Nobody sounds quite like Janis Joplin. I mean, Janis Joplin without the ’60s would have still been Janis Joplin.”

Come on, come on, come on, come on.

Didn’t I make you feel like you were the only man –

Oh, yeah –

Didn’t I give you ev’ry thing that a woman possibly can?

Maybe this is part of it: She was a pioneer, one of the early women in rock-and-roll to go out there big time in front of a band and hang it out all alone. And she slung it from the heart – and isn’t it the stuff of the heart, far more than of the head, that lasts? The privileged intellectual theorists like Timothy Leary seem awfully stale by now, yet the world keeps listening to the collected songs of Joplin. Next month there’ll be a new Joplin CD in the stores: a previously unreleased live concert at Winterland in San Francisco in 1968 with her greatest band, Big Brother and the Holding Company. According to the press release, it’s the “latest entry in the ‘Live From the Vaults’ series of Columbia/Legacy.” Sounds almost ghoulish. Joplin would savor that.

This spring at the University of Texas in Austin there was a course in American Intellectual History, taught by a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian, titled “O Wild Ecstasy – Narcissism and Hedonism in Recent America.” Admission was restricted to 12 graduate students. The high art and tormented life of Janis Joplin was in the syllabus, along with work by Andy Warhol, Norman Mailer, Tom Wolfe, Bret Easton Ellis and Christopher Lasch.

Prof. William Goetzmann taught it, first time he offered the course. He says he just got captured by the life. He’s always loved the music. He’s 67. He says that America’s continuing interest in her perhaps has to do with “resurrecting something of the poignant primitivism of her generation.” In other words, she can get us quickly back. You listen to the songs and it all returns in bites. Goetzmann used to see Joplin throb the blues at a converted Gulf gas station on North Lamar Boulevard in Austin called Threadgill’s. She sang there on Wednesdays for $2 and all the Lone Star beer she could drink. This was in the early ’60s, before anybody outside Texas had ever heard of her, before she lit out for California and eventual Haight-Ashbury dreams.

Briefly, she’d been an art student at U-T. She’d come up to the semi-bohemian college paradise – where there were 20,000 students – from her native seacoast ground of Port Arthur, Tex. In Port Arthur, she’d been a misfit: ever the right thing in a wrong place. She never really fit in at Austin, either, except with her fellow hippies – which was a word nobody had heard yet. Austin in the early ’60s was a bohemia only by degree. The frat boys who ran the place orchestrated a campaign to get her named “Ugliest Man on Campus.” They succeeded.

“Did you entertain in Port Arthur?” a dopey TV interviewer asked her once, when she was back home for her 10th high-school reunion in all her San Francisco garishness: beads, bangles, boas.

“Only when I walked down the aisles,” she cracked.

The same guy tried to press her about high school – football games and proms. “Uh, I didn’t go to the high school prom,” she said.

“You were asked, weren’t you?”

Very slowly: “No, I wasn’t.”

On “The Dick Cavett Show,” she once said: “They laughed me out of class, out of town, out of the state.”

Love, Janis

That other self: It was always there, beneath the music, informing it, and we knew this, we just didn’t want to think about it very much. The other self wanted parental approval. The other self was surprisingly literate. The other self had this curious, fragile, little-girl quality about it. It had something ingenueish and middle-American about it. That the two selves were so impossibly in conflict is what the made the art go, fueled all the destruction.

You want to discover the other self, read the letters. They’ll knock you flat. A bunch of them are in a 1992 book called “Love, Janis.” It’s by Laura Joplin, her younger sister, who lives in Denver and is raising a 12-year-old. The sister has a doctorate in higher education and has done motivational programs and workshops.

But the letters.

“Dear Mother and Dad. Haven’t received any word from you yet but presume we’re still speaking, so another letter. . . . I’ve found a room in a rooming house. Very nice place w/a kitchen & a living room & even an iron & ironing board. . . . Still working w/ Big Brother & the Holding Co. & it’s really fun. . . . We rehearse every afternoon in a garage that’s part of a loft an artist friend of theirs owns & people constantly drop in and listen – everyone seems very taken w/ my singing. . . . Oh, I’ve collected more bizarre names of groups to send – (can you believe these?!) The Grateful Dead, The Love, Jefferson Airplane, Quicksilver Messenger Service, The Leaves, The Grassroots. . . . I’m still okay – don’t worry. Something of a recluse. Haven’t lost or gained any weight & my head’s still fine. And am still really thinking of coming back to school, so don’t give up on me yet. I love you all.”

That’s from June 1966. Two years later, on the edge of going intercontinental with her success, she writes: “Well, here it is – our first New York review from our first New York gig. . . . From all indications I’m going to become rich & famous. Incredible! All sorts of magazines are asking to do articles & pictures featuring me. I’m going to do everyone. Wow, I’m so lucky – I just fumbled around being a mixed-up kid (& young adult) & then I fell into this. And finally, it looks like something is going to work for me. Incredible. Well, pin the review up so everyone can see – I’m so proud.”

To read these letters to the family who lived in the neat, tree-shaded, pink-frame house in Port Arthur is to begin thinking about Joplin in an entirely different way. She’s recommending books to her siblings (Tolkien’s “The Hobbit”); talking about her “budget”; growing rhapsodic over her new dog. She’s named him Thurber, in that she’s always adored James Thurber’s cartoons and stories. To read her letters is to come in contact with a woman out on her own now, questioning ambition.

“After you reach a certain level of talent (& quite a few have that talent) the deciding factor is ambition, or as I see it, how much you really need. Need to be loved & need to be proud of yourself. . . . & I guess that’s what ambition is – it’s not all a depraved quest for position.” As one rock critic has said, it’s pretty weird to think that such thoughts could have been put down – and not insincerely – by a person debauching and debasing herself all over the country.

Laura Joplin speaks cautiously and protectively about the sister who was older by six years. It’s as if she feels no one really wants to hear her. On the phone, there is a certain small scratchy quality in her voice that instantly reminds you of the Joplin no longer here. “I think Janis represents the strength of women on their own. I think it has to do with strength, with independence. I look at Janis as a whole person. Drugs is not something we ever did together. I accept it, I accept all of it. I just can’t connect with it.” She adds: “I understand there’s a lot of ambiguity about her.”

Lone Star

Although California – and in particular San Francisco – is the place the world associates with her name, Texas, and especially Austin, is the better place to try and make contact with her ghost. Janis Joplin is of Texas. It’s where she discovered her lungs, especially in and around the clubs of Austin. And funny, all she ever wanted to do was get out of Texas.

Texas means all kinds of things, of course: cowboys and oil millionaires and big cities and lonely spaces and beautiful pedal-steel music – to name but a few. Joplin’s Texas was Port Arthur, which is deep-water ports and oil refineries. It’s in East Texas. It’s in the so-called Cajun Triangle, bordering southwestern Louisiana. “There’s lot of bowling alleys down there,” she told an interviewer once, explaining how she hustled tips as a waitress in more than one.

She fled the place early, never wanting to look back, rolling up the highway to Austin, in south-central Texas, where there was said to be a little more air. It was only a way-stop. One of those who came with her was a high-school classmate named Tary Owens. He’s a reformed junkie and you can find his name in most of the books about her. He still lives in the state capital and has a small folk record company. You call him up and ask whether they were as cruel to her in Port Arthur as has been described, and he says before the question is finished: “They were outrageously cruel. Terrible cruel.”

And then he says, “Frankly, I was in love with her for most of my life. It was unrequited. It never felt right to try to make moves. Well, we did have one petting episode on a trip back to Port Arthur one time.” He can’t remember where he was when he got the news of her death. He was too strung out.

In Austin, a Joplinite can go out to Threadgill’s, which is now a famous American eatery, and study the pictures of her on the old wainscoted walls. He can go out to Zilker Park, where she once won a vocal contest sponsored by the Austin Parks and Recreation Department. He can haunt the coffeehouses along Guadalupe Street on the west edge of campus. He can find the assembly room in the student union where she and the Waller Creek Boys used to entertain at Thursday night hootenannies.

He can hunt up the address where she flopped on couches and floors for most of her university days, which in truth amounted to less than a year. The building was known commonly as the Ghetto, and it was at 2812 1/2 Nueces St. It was a World War II wooden Army barracks. All the student outcasts of Austin found their way to the Ghetto. The rent was $40 a month. Nowadays there’s an Absolut Vodka billboard across the street. The old hamburger joint, Dirty’s, is still nearby. So is the fraternity house next door. She used to lie in a hammock and hurl obscenities across the yard.

And a Joplinite could also do this: Go to the microfilm rolls in the university library and spool to an old story in the student daily, the Texan, dated July 27, 1962. She’d barely been on campus a month. The headline: “She Dares to Be Different.” The Campus Life editor wrote the piece, and this was the lead: “She goes barefooted when she feels like it, wears Levi’s to class because they’re more comfortable, and carries her Autoharp with her everywhere she goes so that in case she gets the urge to break into song it will be handy. Her name is Janis Joplin.”

There she is, one-column photo, with her autoharp, between ads for unfurnished apartments and loafers at Dacy’s Campus Store, looking so un-Californian, the arms a little fleshy, the mouth struck open in song. She is on her way now, and the way won’t end until the needle in an L.A. motel eight years hence, and even there it won’t end, no, the mouth will ever be hung open with all that power and hurt.