“Scoping Out Baghdad”: Chet Helms was another one of those whose experiences classified them as “outside the norm.” A child evangelist at age 15, he’d been raised in a strict fundamentalist family which forbade dancing, listening to pop music, watching movies. In his late teens he became an ardent civil rights activist, eventually joining the Young People’s Socialist League. Caught up in the “On The Road” romance and eager for escape, he split for San Francisco in 1962. He was 20 years old, a long, tall Texas “poet savant in a beret, little pegged Italian pants, a goatee and mustache.” He spent his first night in a sleeping bag at an anti-nuke picket line at the old Post Office near Seventh and Market, across from the Greyhound station where he arrived. Subsequently, he found a pad, crashed, woke up and went looking for the big beat scene. When he found it, it wanted nothing to do with him.

It might have as well have been an assembly of the Duck River Baptists of the Hutterite Brethren, so tightly did the scene heavies clutch the reins of power. “The local poetry establishment was then more or less dominated by Ferlinghetti and City Lights Publishers,” Helms remembers, “and his people generally determined who got to read where.” Locked out, Helms made an end run around the church elders. Under their upturned noses, he convinced the owners of the Blue Unicorn coffeehouse to let him hold open poetry readings. “It was very democratic. Anyone could come and read their stuff, good, bad or indifferent.” The Unicorn management gave Helms free rein – up to a point. Before long, they were chastising him for his rather “open” experimenting with hallucinogens, a brand new no-no to the now graying bohos.

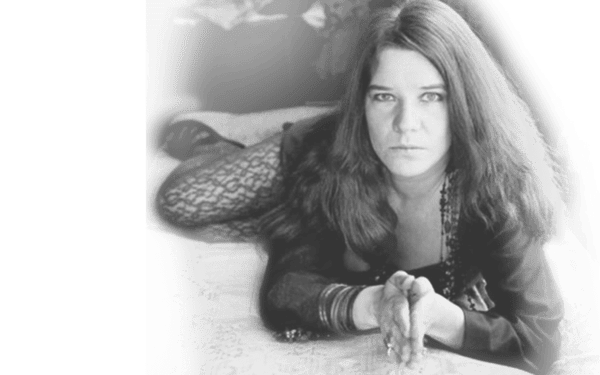

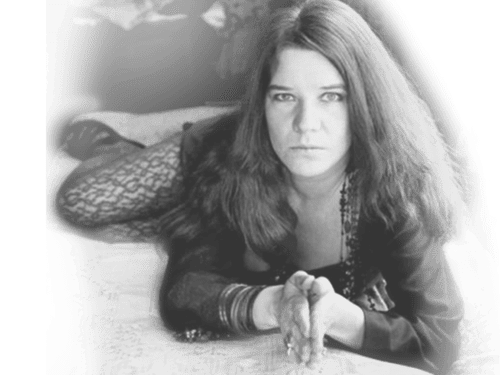

Undismayed, Helms kept at it, scoping out Baghdad for something new. Noticing the “very polished, Kingston Trio-type” folk music scene flourishing in the Bay Area and figuring funky is better, he flashed on a girl he’d met in Austin who belted the blues raw and ragged. “I just thought Janis would knock these people on their ass.” He went back to Texas, found Janis and convinced her to join him on a breakneck 50-hour thumb trip to San Francisco to start her career in earnest.

Janis made a modest dent on the Bay Area folk scene, singing solo and as half of a duo with Airplane guitarist Jorma Kaukonen, at places like Coffee & Confusion. By 1963 she’d even moaned the blues over radio, on one of KPFA’s hoary hootenannies that also featured a scruffy young harmonica man, Rod “Pigpen” McKiernan. She was impressive, undisciplined, and near deafening. “Chet had me come and hear her once at the Coffee Gallery,” Luria Castell remembers. “She was backed by one electric guitar, and she was so loud I had to stand out on the sidewalk.” Eventually Joplin, like scores of others, got hooked on the self-destructive myth of the Beat ethos and fell into a methedrine habit. Fearful for her life, Helms and a bunch of friends took up a collection, threw a farewell party then put her on a Greyhound back to Texas.

By ‘65, Helms’ restless evangelical spirit had found a new mission: pop music. After trying to form his own band, he fell into organizing jam sessions in the basement of 1090 Page Street, a full-gabled, bay-windowed 25-room Victorian mansion a block north of Haight. Ten-ninety was being sub-let to State students, hipsters and hangers-on by Rodney Albin, who was managing it for his uncle – who was waiting out legal red tape for permission to tear it down and let him build the senior citizens project he’d planned. The mansion’s transient population (and the neighborhood’s rapidly de-escalating demographic) assured a constant supply of performers and audience for Helms’ 50-cent Wednesday jams.

“Tom Swift and His Electric Grandmother”: Many of those who sang and played were non-musicians like Helms, and quickly proved it after a turn or two on the plywood stage. Others were proficient ax-men who hung around long enough to figure they deserved better, then split for paying gigs. But the most interesting ones were those who “could play a little.” Like Helms, they were getting their feet wet here, trying on this new, amplified shake-and-shimmy trip. Many were folkniks, toward busting out of stalled careers as junior New Lost City Ramblers or Carolina Tarheels or whatever.

Once the game of musical chairs settled down, these were largely the musicians who comprised the 1090 “house band” in late ‘65: guitarist Dave Eskerson and drummer Chuck Jones (both of whom were shortly replaced), guitarist Sam Andrew, and Rod Albin’s younger brother Peter, an amiable folk ‘n’ bluegrass picker who’d worked the same San Jose Peninsula folk circuit as Paul Kantner and Jorma Kaukonen. Now Peter was learning electric bass and turning into something of a rubber-faced madman – throwing his Prince Valiant locks all over the place, shouting out “Satisfaction” and “Spider and The Fly” down there in his uncle’s basement. And he was writing songs, songs that, if they weren’t as well-crafted as the Stones’, were certainly weirder. There was “Caterpillar” (“I’m a caterpillar, crawling for your love/I’m a pterodactyl, dying for your love”) and one called “Banana” whose sole lyric was the title repeated endlessly over a thundering bass riff. Great googly-moogly!

The band coalesced when David Getz, a student at the San Francisco Art Institute, came in on drums and a Detroit pal of the Family Dog’s, Jim Gurley, was recruited as lead guitarist. “Jim said that his first job was being a human hood ornament on his father’s car in the Thrill Show,” Getz recounts. “They toured around with auto races and demolition derbies. Gurley would be mounted horizontally on the hood with his head out the front; the car was then driven at high speed through a wooden wall that had been set on fire. The first time, he was a little scared and moved ever so slightly just before impact and almost broke his neck. later he learned to keep his head perfectly straight and didn’t feel a thing.” A part-time traveler on the folk circuit, Gurley listed his musical influences as a “combination of Spike Jones and ‘Good Night Irene’.”

The band was ready for action. Helms had signed on as their manager and had publicity photos taken, inside the cable car barn above Chinatown. All they needed was a name. “At first we called ourselves Blue Yard Hill,” laughs Peter Albin, referring to a name suggested by Paul Ferez, a 1090 regular who wrote bad Dylanesque poems and served briefly as the band’s lead singer. “Then we thought about Tom Swift and His Electric Grandmother, but that didn’t really do it either.” It was Helms who took matters in hand, sitting everyone down and inviting them to toss out potential names while his wife, Lorraine, wrote them all down on a notepad. “When we’d run out of names, there was this big long list,” recalls Helms. “Lori read them back to us, and when she got to the last two she accidentally read them together, as one long name: Big Brother and the Holding Company. I yelled, “That’s it! ‘Big Brother and the Holding Company’.” The band fought with me over it. They argued that it was too long a name to fit on a 45 label. They thought there were too many letters for the space.”

“A Moment’s Freakery”: Yet if any one group personified the sheer, perverse freakery of the moment, it was 1090 Paige’s erstwhile basement jammers. Big Brother & The Holding Company. If the Grateful Dead were all mythic strum and drang – a rock & roll Ride of the Valkeries – Big Brother was an cosmic prank, a gaggle of miscreant savants whose jump-started sound lurched and careened with spastic abandon.

Since their Paige St apprenticeship, Big Brother had wandered off into some directions bizarre even by San Francisco standards. “At first we did a lot of cover material, but it all got freaky pretty quick,” recounts bassist Peter Albin. “A big influence was what the other bands were into; we fed off each other. After we’d gone through folk-rock and early Stones stuff, we veered off toward a jazz thing.”

The improv imperative again; but at the hands of Big Brother, it bore no resemblance to anything even vaguely respectable. Some of the band’s early shows highlighted their version of the theme from the Russ Meyer sleaze flick “Faster, Pussycat, Kill, Kill” and an extended jam based on “Hall of The Mountain King” from Tchaikovsky’s Pier Gynt Suite. “We’d do six bars and then go into something different every time. At the end we’d come back to the theme and James would shake his Danelectro amp for a funky reverb effect that sort of sounded like thunder, you know, in the spirit of the piece. We were never really into jazz. We thought we were, but we could never play a single jazz lick.”

And precious few traditional rock licks, either. The mainstay of the band’s early incarnation was the berserk guitar playing of Jim Gurley. “He reflected a lot of the sounds and noises and dissonances that were his childhood and it was wonderful,” asserts Chet Helms. “He could make sounds like breaking glass on guitar and it was somehow still rhythmic. There was something fresh and innovative about him that was, in some ways, diminished by the demands that people put on him to become a formal musician.”

Maybe. But by mid-’66, there was nothing holding Gurley back – certainly not the niceties of musical etiquette. The sounds he coaxed from the guitar on songs like “Light Is Faster Than Sound” were indeed the aural equivalent of bent wires, broken windshields, overheated metal and screeching rubber; the whole super-charged ambience of his destruction derby youth. “He used to play the national anthem to open up the races,” Helms reports of Gurley’s early musical education.

Once on stage, however, while Gurley stood like a golem with blurry fingers, it was bassist Peter Albin who commanded attention. Wearing, more often than not, a black frock coat, he would shout his songs into the microphone like a Romilaraddled frog, leaping and twirling, exhorting the crowd in his alter-ego as “The LSD Preacher.” “I did a thing tacked onto “Amazing Grace,” Albin recalls, “which was an improvised rap about a guy getting psychedelicised…he goes into church and this ranting priest gives him “the sacrament.”

“Since they had less of a mastered, polished approach, they could sometimes do really interesting stuff and make it work,” recalls Jack Casady. “They’d play solos or some combination of notes that, if you’ve ever played live music you’d never think of doing, but somehow it worked. You’d scratch your head and think “it works,” but what key is the guy in?”

Not surprising that the band got more than its share of strange gigs. Until they were replaced by the Dead, Big Brother had been adopted as the house band for the Frisco chapter of the Hell’s Angels and did a number of party/benefits for the motorcycle gang, along with innumerable one-off event and happenings. “We once did an art show called Blast,” remembers Albin. “There were a lot of weird acts, including a black woman who played piano and sang to comic strips, mostly Flash Gordon. She’d use the lines from the balloons as lyrics; you know, like “Flash, you can’t go into that cave!” and there were dancers behind her, going back and forth on swings.”

“Janis Arrives”: There’s no telling to what extremes of strange the group might have gone to if left to their own devices. But with the addition of a final member, in May of 1966, Big Brother – along with the rest of the rock ‘n’ roll world – would never be the same. “We talked about getting a vocalist very easy,” recalls Chet Helms. “I suggested Janis, but both Peter and Jim said, “No, we saw her at the Coffee Gallery and she’s too weird.” I didn’t pursue it. But we couldn’t find anyone else that measured up, so I suggested tracking her down again.”

Janis Joplin was, in fact, back home in Austin, healthy again after a sustained absence from drugs and the frantic pace of the San Francisco underground. “She was very concerned about getting back into drugs again,” Helms continues. “I did my best to assure her that everyone had cleaned up from the hard stuff. It was LSD, a very different thing. She came back, and the first few times she sang with the band, they weren’t sure it was going to work out.”

Not so, claims Albin. “We didn’t really audition her,” he insists. “Jim and I had seen her before and persuaded the others to bring her back. “she’d good, she’ll work,” we kept saying. “we know you’re gonna like her.”

Considering what Janis Joplin was to mean to Big Brother and, very quickly, the whole San Francisco music scene, it’s small wonder that both Albin and Helms claim credit for recruiting her. Whatever the actual circumstance, Joplin returned to the city on June 5th and immediately began rehearsing with the band at their Henry St digs. The group’s first performance with their new vocalist was on June 10, 1966 at the Avalon Ballroom. She sang only two songs during the whole set, sitting out the lengthy freak-rock interludes atop an amplifier, banging a tambourine.

“I wasn’t a strong singer.” admits Albin, “and the fact was girl vocalists were an added attraction to bands at that time. We worked with her a couple of weeks, maybe less before the show.” Albin says that after Janis joined, the group began a verse-chorus-verse regimen to showcase her considerable vocal skills and turned down the volume, when her throat began to giving out from he shouting above the din. She also insisted on better equipment, particularly an upgraded P.A.

“She brought a lot of songs with her,” Albin continues. “Women Is Losers” and the Chantel’s “Maybe.” We used to do a duet on “Let The Good Times Roll” and “High Heel Sneakers.” After the first couple of shows with their first out-of-town gig down to Monterey, the group began getting comments from old-line (and hardcore) fans. “You guys are losing the craziness,” is how Peter Albin remembers the reaction. “You’re getting more like all the other bands in town. Get rid of the girl.”

But if Janis was changing Big Brother, Big Brother was having a similar effect on Janis. “Vocally she started out with a very acoustic sound,” explains Peter Albin. “It was very full and, in a lot of ways, very folksy, like Bessie Smith on some songs.” One of the first times Albin had seen her was during her early trip to the coast, when she performed on a radio show called “Midnight Special,” on station KPFA. “Everyone sat around a mike, kind of hootenanny style,” he continues, “The Chambers Brothers were there, doing acapella gospel and I remember this kind of plumpish broad in a man’s button-down shirt, no bra and a pock-marked face. She’d close her eyes when she’d sing and she had a lot of soul.”

“She was a very folk-oriented person,” concurs Mike Pritchard, who spent time with Joplin around the same period. “She knew about her roots and was very serious about her intentions. I remember playing guitar with her. I was very into art music and she wanted to sing the blues. I was trying to play along and she just looked at me and said ‘That’s not the blues.’ ‘It’s the right notes.’ I said. ‘Yeah,’ she insisted, ‘but it’s not the blues.’”

Three years later she was revved up and ready to match the wailing electric energy of Big Brother. “She had to change her vocal style,” Albin continues. “It became much less colored. The range she had when she sang at low volume was fantastic, but she really had to push for that range with a rock ‘n’ roll band. Towards the end of her first year with us, she started getting nodules on her throat. You could hear two or three overtones in each note.”

“Pieces of Hearts”: You could almost hear the consuming passion that scorched the ears of the ballroom denizens. By the end of the summer, the billing, in most people’s mind, was already ‘Janis Joplin and Big Brother.’ Whether she was transfiguring blues and R&B chestnuts or adding her keening moan to Big Brother’s skewered originals (numbers such as Dave Getz’s “Harry” or a yodel epic called “Gutra’s Garden”) Joplin had become the group’s larger-than-life focus. Tunes such as “I Know You Rider” or Erma Franklin’s “Piece of My Heart” (a song suggested by Airplane bassist Jack Casady) were driven to raw emotional extremes by her flayed, ragged voice. Hunched over the microphone, her hands clutched and her hair falling into her face, she seemed, at times, peculiarly out of place in the paisley utopia of the psychedelic scene. The doomed urgency in her voice, shrill and hoarse by the end of every performance, unsettled the nonstop revelry.

“One day we all piled into a car, drove over to Marin, picked up a newspaper and looked up ‘Houses for Rent,’ Dave Getz was to write, years later. “that same day e found a big house in the little town of Lagunitas…it was a beautiful day. Everything seemed to work out right. Nothing could go wrong; God had taken care of us perfectly…The house was at the end of a road way back in the woods with no other houses around it. On a big butane tank coming up the driveway, someone had scrawled ‘God is Alive and Well.’ Later another had added ‘In Argentina.’ Eventually our house became known as ‘Argentina.’

“…Janis had a lovely, sunlit room like a porch which she decorated with plants. Like the room, she became her most peaceful and beautiful self during that time…”

“A lot of the early bands were just a collection of friends,” ruminates Jerry Garcia, “some of whom could play instruments, some of whom couldn’t. Later on, bands were constructed – put together for every specific purpose. Sometimes it was a manager’s concept, sometimes a musician who wanted a certain kind of sound and went out and auditioned until he found the right people.”

“The Texas Factor”: “In the sixties,” explains Chet Helms, “the repression in Texas was so severe that to escape it you had to create these vivid mental spaces, so I think you find in Texas some really strong characters with really vivid imaginations, really creative people who’ve found a way out of that repression to make a place for themselves, for their own sanity. I will always feel a very strong kinship for all the people who’ve escaped Texas.”

“Microscopic Royalty Rates”: Big Brother’s particular version of Beelzebub was Bob Shad – another A&R man from a Chicago jazz label called Mainstream. Peter Albin: “Chet Helms heard about an audition Mainstream was holding in San Francisco and got us into it. To other groups were trying out – Final Solution and Wildflower. Shad was there and he had a long talk with Chet. Shad told us to come with him to Chicago where he’d sign us and get us gigs playing in local clubs.” Once in the Windy City, the band was at the mercy of a host of sleazy shysters, including one club owner who booked the band for a one month stand. “After three weeks,” recalls Albin, “he told us, ‘I can’t pay you what I owe you. I don’t know what to do about it, but I’m open to suggestions,’” The band’s suggestions are better left unrecorded…besides, they had other worries. Since their arrival, Shad had been slurring Chet’s Helms in no uncertain terms. “He said Chet tried to sell us down the river, and that he was the only one who could insure that we got a good deal with the record company,” continues Albin. “we said ‘Well, we don’t have representation.’ and he got us a lawyer…his lawyer.”

Before it was over, Big Brother had signed a deal with Mainstream for no advance and a microscopic royalty rate. t was, as it turned out, only the beginning of their troubles. “the whole thing was cut in two evenings in Chicago and two day sessions in L.A.,” Albin sighs. “Shad produced. We weren’t allowed in the mixing booth and he never let us do any more than thirteen takes. He said it was unlucky to go past thirteen.”

The ten resulting cuts were released as an eponymously-titled album in the fall of ‘67. It succeeded, against almost impossible odds, in capturing much of the band’s quirky, makeshift exuberance and was compelling evidence of Janis Joplin’s considerable vocal skills long before her fame as a blues banshee. Big Brother & the Holding Company was a mild Bay Area hit and a national nonentity, despite the insistence of the liner notes that “you will be amazed at the gamet of emotional sounds this group produces.”

“Cheap Thrills”: The days, not so long before, when the originators had to go, cap-in-hand, to the business big shots for a chance to ‘Please, sir, may I cut a few sides,’ seemed as long ago and far away as the rent parties and basement jams that had started it all. The crucial chores of management were no longer relegated to old friends; for big Brother & The Holding Company, Chet Helms had been decisively displaced; first by the mysterious Chicagon Jules Karpen, and eventually by Albert Grossman. “He had a lot of solid pop bands,” says Albin, “groups like the Paupers, and the Pozo Seco Singers. We were nothing like them. We were psychedelic rangers.” Janis Joplin was, however, being touted as the closest thing to Billie Holiday the white race would ever produce, and Grossman was hardly the first to try and pull her away from the ranger corps. Back during Big Brother’s Lagunitas tenure, when Janis had first been recruited in 1966, she had been approached by Electra’s Paul Rothschild. “He told her he wanted to talk with her, that he thought he could get something going for the band,” reports Albin. “It turned out he wanted to put together a supergroup around her with Taj Mahal and some other people. She was two months out of Texas and here he was offering the world on a platter. she didn’t know what to do; she started to crying. She was really torn; you know, we were all living together, we were a family. That’s one of the reasons we took the Mainstream deal. We thought it would lock Janis into the group.”

It was a lock being picked with subtle skill by Albert Grossman. “He didn’t like the band,” Albin states flatly, “especially Dave and me. We started recording our CBS album and he said, ‘I hope this doesn’t offend you guys, but I think we ought to bring in some other people for the recording’ We said, ‘as a matter of fact it does offend us.’ But Grossman kept working on Janis. ‘Even if Dave and Peter don’t play on the album, they can still make a lot of money,’ he told her.”

“Cheap Thrills,” Big Brother’s trumpeted debut on Columbia, was originally planned as a live recording. The band had played a three night stand at the Grande Ballroom in Detroit, recorded by Elliot Mazur and John Simon, the producer Grossman had hired for the sessions. “It didn’t sound so good,” recalls Albin, “so we tried to get a ‘live’ sound in the studio by keeping the overdubs to a minimum.” Eventually, Simon mixed in ballroom ambiance and an introduction by Bill Graham. Released in September of ‘68, “Cheap Thrills” sold a million copies as fast as they could be pressed. As a musical document it chronicles Joplin’s rapid overshadowing of the group – with her unvarnished vocals pushed way to the front on blues workouts like “Ball & Chain” and “Summertime” the group sounded shoved into a corner, tinny and ineffectual against the unrestrained energy of their singer’s performance. It was a telling symbol of the band’s rapid disintegration. By early the following year Janis had left the band, following The Grey Cloud to certain stardom.

Mike Pritchard saw the lines between commerce and creativity become blurred. “Janis was fine as long as she was just a person, ‘doing her thing.’ As soon as she defined herself, that put her into the nexus of show biz. that move had implications nobody expected.” Least of all family Dog founder Luria Castell. When she returned from Mexico in early 1967 to the thriving scene she’d help birth, it was barely recognizable. “Part of me said I want to be involved, but then I realized, like the Stones said, you can’t come back and be first in line. Later I went to Winterland and it was packed, but there were no vibes, it was a vacuum. It was crazy, with all that energy and none of it being released. It had nowhere to go.”

Jerry Garcia: “It started out going in a much more interesting direction than it ended up. I could never understand that.”